ArchivedThis page has been archived. It is provided for historical reference only.

If you were unable to attend the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health’s all day conference, Health Effects of Shale Gas Extraction: What is known, and what can we predict?, here is a recap of the morning sessions for you provided by CHEC’s staff.

Program | Morning Summary (below) | Afternoon Summary | Presentation Videos | Survey Results

“Health and Safety Considerations in the Extraction of Fossil Fuels”

Bernard Goldstein, MD is a professor in GSPH’s Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, as well as the school’s past dean. Dr. Goldstein started off the conference with a discussion about the need for public health, government, and industry to use proper risk communication techniques when discussing risk of natural gas drilling with the public. For example, if the industry had openly discussed the ingredients of the fluid used to hydraulically fracture the shale and the purposes of those ingredients when hydraulic fracturing was first used, for example, it would have prevented a significant amount of [often times] unnecessary fear regarding the fact that the exact composition of each company’s well stimulation mixture is proprietary (a trade secret).

Additionally, Dr. Goldstein called for public health to conduct prospective research on the potential public health impacts of shale gas drilling, because it is difficult to make connections retrospectively (looking back).

He also noted that Pennsylvania is at disadvantage when it comes to our public health workforce (the folks with the expertise and know-how to look out for the welfare of PA residents). – Only 6 of 67 counties in PA have a public health authority, and we have the smallest workforce in this field of any state in the U.S. In essence, “PA is a third world country in relation to its inadequate public health workforce.”

“Inorganic Geochemistry of Marcellus Shale Hydrofracturing Waters”

Carl S. Kirby, PhD began his presentation by defining the terms “slick water” and “frack-water”, since the chemistry of each is so different. Slick water consists of water, proppant, and slicking agents that are pumped down into the drilled well. Frack water identifies the liquids returning up to the surface after hydrofracturing has been completed. This liquid includes the slick water, as well as a concentration of brine water from within the well. The concentration of brine is largely irregular, and depends upon the geochemistry of the drilled strata, and the amount of time the slick water remained in the well bore, before returning as frack water. The extent of dissolution of salts/brines in the frack water is a major concern, since the current treatments of frack water do not provide an assurance that these chemicals can be removed from the frack water. Therefore, the options for frack water are storage, recycling and reusing, transporting the frack water to be treated at specialized facilities, or reinjection. Much of the frack water goes to Ohio where it is injected into deep wells – a method the industry calls a “closed loop.”

The chemical characteristics of frack water are dominated by high TDS, specifically: Na, Ca, Cl, Ba, Sr, and low concentrations of Mg, SO4. The frack water is radioactive, and has a pH in the 5-8 range, which is rather neutral. A Durov diagram was presented to show the signature of anions and cations. Some frack waters are also 1/3 solids. The volume of flowback frack water is very high at first and then slows down while salinity is thought to increase dramatically with time, although there is currently not enough data to confirm the increasing salinity. The radioactivity was investigated; the gross alpha is typically due to radon gas, which is short-lived. The gross beta on the other hand is of higher concern, as it typically signifies radium, which remains particulate-bound.

Technologies are available to characterize certain aspects of the drilling, fracking, and production phases of natural gas production. Hydro-geological modeling with the geochemical program PhreeqC has been conducted by Dr. Kirby’s work group. Modeling results indicate that the main source of iron (Fe) is pyrite, while the main source of barium (Ba) is from organic acids. Other techniques are also available to help prevent environmental degradation. Using conductivity to investigate leaks in the frack water infrastructure is a possibility, but one would have to be careful when interpreting changes in surface water quality. In particular, conductance is non-specific, and there is also the potential for lack of mixing in surface water such that the monitors miss the event.

“Trace Metal Chemistry of the Marcellus Shale”

Tracy Bank, PhD discussed the chemistry of the Marcellus, beginning with the geology of the formation. Shale is a sedimentary (meaning deposition) rock type consisting of a fine-grained composition of a mixture of minerals. Though mostly clay minerals exist, metals species can exist in varying amounts. The Marcellus Shale is considered a black shale that was formed in relatively deep waters, devoid of oxygen. Trapped decaying matter in and around these areas nearly 400 million years ago lent to the conservation of natural gas, oil, and coal. Conditions that conserve organic matter also favor the conservation of redox sensitive metals such as; iron, zinc, molybdenum, and uranium.

The solubility of metals, meaning the ability to form a homogeneous solution or become mobilized with water (solvent) for instance, is partly dependent on the amount of oxygen, amount of pressure, and availability of a solvent. Dr. Bank’s research focused on the solubility of uranium, and in her presentation on Friday, she explained that the solubility of uranium is dependent upon redox conditions. Also the concentrations of uranium, for instance, are higher where there are higher levels of total organic carbon, and higher levels of natural gas is certainly what industry is seeking. Redox reactions, in short, describe the changing of a molecule’s oxidation number, commonly in the form of a gain or loss of electrons.

Dr. Bank presented that the shale layer and rock formations thousands of feet underground, are surely lacking oxygen, and thus are in a reducing redox state. When large amounts of pressure and water are introduced into these underground formations by fracing, the oxidation states and reducing conditions can be altered leading to the mobilization of uranium, iron, and zinc. This can and does happen naturally to rock layers exposed to weathering, as it does in the Marcellus Shale outcrops. Dr. Bank’s previous work, focused on Superfund sites containing relatively much higher levels of uranium and other radioactive contamination. Interesting to note, that in those projects – to clean contaminated areas – the bioremediation efforts focus on creating reducing redox conditions; the opposite of what fracing induces.

“Unconventional Gas Extraction in Legacy, Energy Production Landscapes: Uncertainties in History, contamination, and Interactions”

Dan Bain, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Geology and Planetary Science at the University of Pittsburgh addressed the correlation of Southwestern Pennsylvania’s legacy landscapes and natural gas extraction. An important public health concern is the potential for the interaction of varying water compositions used in the Marcellus Shale production process and mobilization (or movement) of metals through legacy surface sediment i.e. sediment resultant from the effects of coal mining on the region. According to Dr. Bain, sediment drives most chemical interactions at the water-sediment interface. Therefore, it is critical to continue to monitor ground and surface water for increases in metal content. The mobilization of sodium is of particular concern to riparian ecosystems.

As coal mining left its imprint on the region, gas extraction from Marcellus Shale will undoubtedly leave another set of legacy sediment types. Dr. Bain proposes that continued research regarding comprehension of flood plains and near surface bed rock is necessary to appropriately model possible outcomes from movement of industry specific waters through legacy sediment.

“Water Management Challenges in Marcellus Shale Gas Production”

John Veil presented information based on his work funded by the U.S. Department of Energy. First, background information about shale gas and how it is developed was presented. The types of gas exploration include coal bed methane, conventional on-shore and off-shore, gas associated with crude oil, unconventional on-shore, and net imports. Mr. Veil stated that the contribution of shale gas is bound to expand. Shale is located in many places in US, and the most significant are the: Barnett (Texas), Fayetteville (Arkansas), Antrim Shale (Michigan), Haynesville (Louisiana), Marcellus (Northeast U.S.), and Woodford (Oklahoma). There are also shales located in Canada, the Horn River Shale in British Columbian, and Nontney Shale in British Columbia and Alberta. The steps in the shale gas extraction process include: gaining access to the gas through property leasing or acquisition, searching for natural gas, preparing the site, drilling the well, preparing a well for production (includes hydraulic fracturing), and finally gas production and water management.

Mr. Veil then elaborated on water issues:

- During site preparation, storm water runoff should be considered from all land areas disturbed during construction, which includes following proper sediment control practices and stabilizing exposed surfaces (generally prepared with gravel). Different operators follow different degrees of storm water management.

- Water is also necessary for the drilling fluids and can range from 1 million gallons in the Haynesville Shale to 60,000 gallons in the Fayetteville Shale. The amount of water depends on the types of drilling fluids used and the depth and horizontal extent of the wells. The Marcellus Shale drilling volume falls near the lower end of this range at 800,000 gallons per well. Drilling waste is then sent to lined pits.

- Hydraulic fracturing is another major water issue. The water needed for a single well in the Marcellus region may require 1 to 5 million gallons. Individual well volumes of water are generally not a critical issue, but collectively can be important within a region. Sources of water can be a stream, river or lake, ground water well, impoundment created by the producer, and a public water supply. Pipelines or tanker trucks (more often) can deliver water to the site. Water is then deposited in impoundments or tanks.

Fracturing (or stimulation) of the well, involves pumping large volumes of water, sand, and additives under high pressure into the well in stages. This process is monitored in real-time, recording the pressures and temperatures during each stage. After fracturing is complete, there is a period of time where water will flow back to the surface in two stages. First, there is the large volume of “flow back fluids” that return to the surface in the first few hours or days, typically collected into pits or ponds. Some larger sites collect flow back fluid in brine tanks where it is filtered and reused to fracture other wells. The second stage is when the “produced water” returns to the surface, slowing in volume over time. This low flow is stored in tanks and picked up by tanker trucks. Collected water must be removed from site by tank truck and hauled off site to commercial disposal wells or waste water treatment plants. Injection wells are another method of disposal. Commercial injection wells are not viable solutions in PA, but there are several in Ohio, causing high truck traffic back and forth between the states.

Mr. Veil discussed how much water would be needed in a high production year. He stated that it is hard to predict the maximum number of wells, but that the report by the United States Geological Survey (USGS), goes back to the year 2005 and does accurate measurements. The totals for the three states of PA, WV, and NY are about 25 millions of gallons/day. The total water withdrawal is 7,457 million gallons per day annually, which means that less than 1% of the total water supply is used. That means there is ample water in the Marcellus region for well drilling, but water needs and considerations will differ according to geographic location and the season.

“Long-Term and Cumulative Assessment of the Impact of Marcellus Shale Drilling”

Michel Boufadel, Ph.D., P.E., Chair of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering from Temple University, spoke about factors leading to the movement and retention of flowback water in his presentation. Dr. Boufadel indicated that this can happen from the bottom of the well up during injection and fracturing, as well as from the ground down in the case of pit leaks.

Although the typical Marcellus Shale well is 7,000 feet deep, the earth is highly fractured, and when the flowback water is injected or hydraulically fractured at pressures up to 10,000 psi (pounds per square inch), it is possible for this water to migrate up thousands of feet, depending on the connectivity of the faults and joints.

The other method for flowback water migration is the possibility of pit spills. Dr. Boufadel stressed that most current models are inadequate, because they do not account for the high density of the brine. Because of this, the flowback water tends to seep deeper in the ground than fresh water would, and remain in the aquifers longer. In addition, shallow sensors may not be able to detect the contamination for years.

Conversation with participants about the gaps in the science and future directions from the morning speakers

Radisav Vidic, PhD, PE was the moderator for the morning sessions. Dr. Vidic did an exceptional job guiding the speakers and discussions with the audience, despite the tensions present. The first part of this session involved summarizing the morning’s presentations. During the second part of his session, participants were given the opportunity to ask questions and provide their input on what seems is missing from the repository of shale gas research.

Questions and Research Gaps Identified by the Audience:

- Translation of data to information is important. We need to assemble cohorts (research groups) to gather background information in order to guide proper risk communication.

- Companies dealing with “frac water” (the fluids produced after wells are stimulated) are promising that their water purification techniques can produce potable water and salt (e.g. for deer licks). What is the quality of the water coming out of these plants? Is the salt safe for animal consumption or use on the roads during wintertime? How should the components of the treated fluids that their systems claim to be able to filter out be handled?

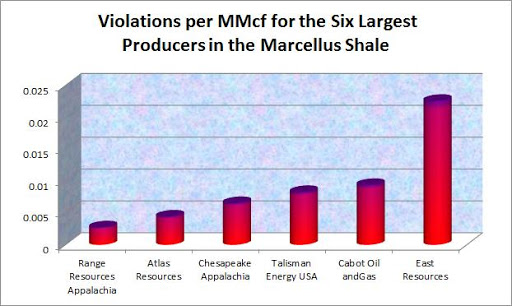

- Secretary Hanger of the PA DEP has referred to drilling companies as A, B, C students, meaning that some are better than others. Regardless, all of the companies have caused violations in PA.

- The time between peer review and addressing community concerns is too much. Additionally, people have trouble understanding what peer reviewed research actually says anyway.

- Has anyone calculated the amount of carbon dioxide we’ve put into the atmosphere from these operations collectively from the beginning of the process to the end?

- Would you like to contribute your own comments about the conference? A link to the survey will be available soon.

Conference Summary Blog Post Contributors

- Charles Christen, DrPH, MEd

- Kyle Ferrar, MPH

- Shannon Kearney, MPH, CPH

- Matt Kelso

- Samantha Malone, MPH, CPH

- Drew Michanowicz, MPH, CPH