The North Dakota Shale Viewer Reimagined: Mapping the Water and Waste Impact

We updated the FracTracker North Dakota Shale Viewer with current data and additional details on the astronomical levels of water used and waste produced throughout the process of fracking for oil and gas in North Dakota.

As folks who visit the FracTracker website may know, the fracking industry is predicated on cheap sources of water and waste disposal. The water they use to bust open shale seams becomes part of the waste stream that they refer to by the benign term “brine,” equating it to nothing more than the salt water we swim in when we hit the beaches.

Some oil and gas operators like SWEPI and Enervest in Michigan, however, have taken to calling their waste “SLOP” (Figure 1), which from my standpoint is actually refreshingly honest.

Fracking Energy Return on Investment 2012 – 2020

Since we created our North Dakota Shale Viewer on October 5th, 2012, much has changed across the fracking landscape, while other songs have remained the same. Both of these truths exist with respect to fracking’s impact on water and the industry’s inability to get its collective head around the billions of barrels of oftentimes radioactive waste it produces by its very nature. From the outset, fracking was on dubious footing when it came to the water and waste associated with its operations, and we have seen a nearly universal and exponential increase in water demand and waste production on a per well basis since fracking became the highly divisive topic it remains to this day.

Figure 1. Oil & Gas waste tank operated by SWEPI and Enervest at the Hayes pad, Otsego County, Michigan May 21st, 2016 (44.892933, -84.786530). Photo by Ted Auch, FracTracker Alliance.

Environmental economists like to look at energy sources from a more holistic standpoint vis a vis engineers, traditional economists, and the divide-and-conquer rhetoric from Bismarck to the White House. They do this by placing all manner of energy sources along a spectrum of Energy Return On Energy Invested (EROEI).

Since the dawn of the fracking revolution, shale gas from horizontal wells has been near the bottom of the league tables with respect to EROEI which means it “…has decreased from more than 1000:1 in 1919 to 5:1 in the 2010s, and for production from about 25:1 in the 1970s to approximately 10:1 in 2007” for US oil and gas according to Hall et al. (2014). This is what John Erik Meyer has come the “EROI Mountain” whereby we’ve already “burned through the richest resources.”

It stands to reason that if natural gas from fracking were a real “bridge fuel” in the transition away from coal, it would at least approach or exceed the EROEI of the latter, but at 46:1 coal is still four times more efficient than natural gas. However, it must be said that coal’s days are numbered as well. Witness the recent bankruptcy of coal giant Murray Energy, and the only reason its EROEI has increased or remained steady is because the mining industry has transitioned to almost exclusively mountaintop removal and/or strip mining and the associated efficiencies resulting from mechanization/automation.

The North Dakota Shale Viewer

We enhanced our North Dakota Shale Viewer nearly eight years since it debuted. This exercise included the addition of several data layers that speak to the above issues and how they have changed since we first launched the North Dakota Shale Viewer.

It is worth noting that oil production in total across North Dakota has not even doubled since 2012, and gas production has only managed to increase 3.5-fold. However, the numbers look even worse when you look at these totals on a per well basis, which as I have mentioned seems to me to be the only way reasonable people should be looking at production. Using this lens, we see that production of oil in North Dakota on a per well basis oil is 1% less than it was in 2012 and gas production has not even doubled per well. This is a stunning contrast to the upticks in water and waste we have documented and are now including in our North Dakota Shale Viewer.

Water Demand Rises for Fracking

We’ve incorporated individual horizontal well freshwater demand for nearly 12,000 wells up to and including Q1-2020. The numbers are jaw dropping when you consider that at the time we debuted this map North Dakota, unconventional wells were using roughly 2.1 million gallons per well compared to an average of 8.3 million gallons per well so far this year. This per well increase is something we have been documenting for years now in states like Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia.

Learn More

For more analysis around water used for fracking, see “The Human Right to Water and Unconventional Energy,” a paper co-authored by Dr. Ted Auch with partners in the UK.

This is concerning for multiple reasons, the first being that if fracking ever were to rebound to its halcyon days of the early teens, it would mean some of our country’s most prized and fragile watersheds would be pushed to an irreversible hydrological tipping point. Hoekstra et al. (2012) have come to call this the “blue water” precautionary principle whereby “depletion beyond 20% of a river’s natural flow increases risks to ecological health and ecosystem services.”

Another concern is that while permitting in North Dakota has slowed like it has nationwide, the aforementioned quarterly water usage totals per well are now 5.25 times what they were in October 2012 and the total water used by the industry in North Dakota now amounts to 60.43 billion gallons– that we know of — which is nearly 50 times what the industry had used when we created our North Dakota Shale Viewer (Figure 2).[1]

With respect to the points made earlier about the value of EROEI, this increase in water demand has not been reflected in the productivity of North Dakota’s oil and gas wells, which means the EROEI continues to fall at rate that should make the industry blush. Furthermore, this trend should prompt regulators and elected officials in Bismarck and elsewhere to begin to ask if the long-term and permanent environmental and/or hydrological risk is worth the short-term rewards vis à vis the “blue water” precautionary principle, in this case of the Missouri River, outlined by Hoekstra et al. (2012). It is my opinion that it most assuredly is not and never was worth the risk!

The most stunning aspect of the above divergence in production and water demand is that on a per well basis, water only costs the industry roughly 0.46-0.76% of total well pad costs. This narrow range is a function of the water pricing schemes shared with me by the North Dakota Western Area Water Supply Authority (WAWSA). This speaks to an average price of water between $3.68 and $4.07 per 1,000 gallons for “industrial” use (aka, fracking industry) by way of eight depots and “several hundred miles of transmission and distribution lines” spread across the state’s four northwest counties of Mountrail, Divide, Williams, and McKenzie.

Figure 2. Average Freshwater Demand Per Well and Cumulative Freshwater Demand by North Dakota fracking industry from 2011 to Q1-2020.

Increasing Fracking Waste Production

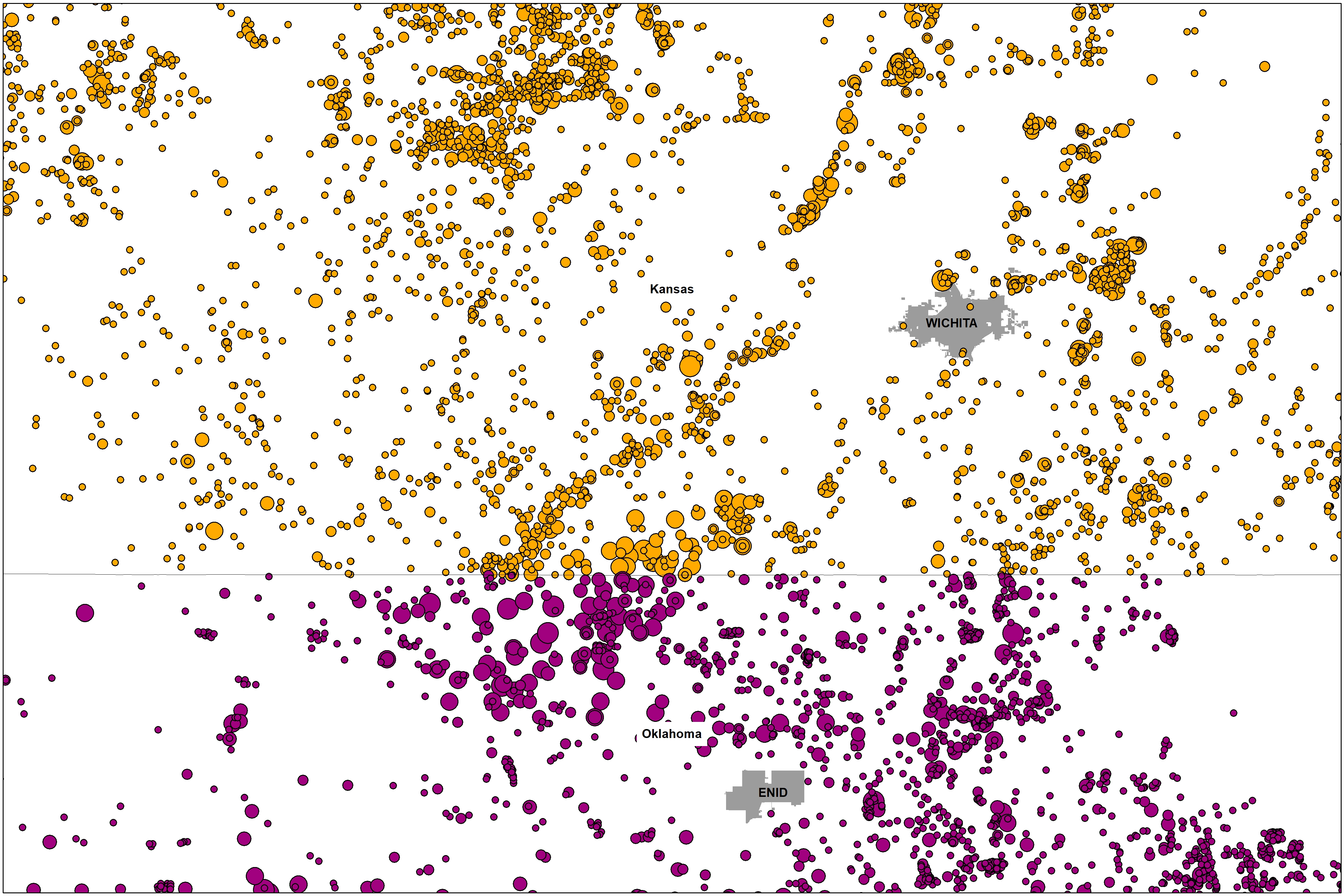

On the fracking waste front, the monthly trend is quite volatile relative to what we’ve documented in states like Oklahoma, Kansas, and Ohio. Nonetheless, the amount of waste produced is increasing per well and in total. How you quantify this increase is quite sensitive to the models you fit to the data. The exponential and polynomial (Plotted in Figure 3) fits yield 4.76 to 9.81 million barrel per month increases, while linear and power functions yield the opposite resulting in 1.82 to 10.91 million-barrel declines per month. If we assume the real answer is somewhere in between we see that fracking waste is increasingly slightly at a rate of 1.51% per year or 460,194 barrels per month.

Figure 3. Average Per Well and Monthly Total Fracking Waste Disposal across 675 North Dakota Class II Salt Water Disposal (SWD) wells from 2010 to Q1-2020.

North Dakota has concerning legislation related to oil and gas waste disposal. Senate Bill 2344 claims that landowners do not actually own the “subsurface pore space” beneath their property. The bill was passed into law by Legislature last Spring but there are numerous lawsuits working against it. We will have further analysis of this bill published on FracTracker.org soon.

Earthworks ND Frack Waste Report

FracTracker collaborated with Earthworks to create an interactive map that allows North Dakota residents to determine if oil and gas waste is disposed of or has spilled near them in addition to a list of recommendations for state and local policymakers, including the closing of the state’s harmful oil and gas hazardous waste loophole. Read the report for detailed information about oil and gas waste in North Dakota.

The Value of Our Water

This data is critical to understanding the environmental and/or hydrological impact(s) of fracking, whether it is Central Appalachia’s Ohio River Valley, or in this case North Dakota’s Missouri River Basin. We will continue to periodically update this data.

Without supply-side price signaling or adequate regulation, it appears that the industry is uninterested and insufficiently incentivized to develop efficiencies in water use. It is my opinion that the only way the industry will be incentivized to do so is if states put a more prohibitive and environmentally responsible price on water and waste. In the absence of outright bans on fracking, we must demand the industry is held accountable for pushing watersheds to the brink of their capacity, and in the process, compromising the water needs of so many communities, flora, and fauna.

Data Links

- Water Usage for nearly 12,000 fracked laterals in North Dakota up to and including April, 2020. We also include API number and operator in GIS, KML, and Spreadsheet formats. (https://www.fractracker.org/a5ej20sjfwe/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/ND_FracFocus_April_2020_With_KML_Excel.zip)

- Monthly volumes (2010 to 2020) and demographics for surrounding area for the 675 Class II Salt Water Disposal (SWD) Fracking Waste Injection Wells in North Dakota. We also include API number and operator in GIS, KML, and Spreadsheet formats. (https://www.fractracker.org/a5ej20sjfwe/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/ND_ClassII_Well_MonthlyWaste_2010_Q2_2020_Demographics_WithKML_Excel.zip)

- North Dakota Gas Plants (https://www.fractracker.org/a5ej20sjfwe/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/GasPlants_WithExcel_KML.zip)

[1] Here in Ohio where I have been looking most closely at water supply and demand across the fracking landscape it is clear that we aren’t accounting for some 10-12% of water demand when we compare documented water withdrawals in the numerator with water usage in the denominator.

By Ted Auch, PhD, Great Lakes Program Coordinator